- The Japanese prefecture has focused on reconstruction since meltdowns at TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station, caused by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami

- Ongoing efforts include decommissioning the nuclear power station, rebuilding infrastructure, reopening communities and ensuring the safety of local residents

It is a date that many in Japan will never forget. March 11, 2011, began just like any regular Friday, but at 2.46pm, Japan experienced the strongest earthquake in its recorded history. The epicentre was in the Pacific Ocean, 130km (80 miles) off the coast from Sendai, a city on Honshu, Japan’s largest and most populous island.

Although Japan was well prepared for earthquakes in light of its location between three tectonic plates, no one could have foreseen what happened next. The 9.0-magnitude Great East Japan Earthquake – powerful enough to shift the Earth off its axis – triggered a tsunami that wiped out many towns along the coastal area of Tohoku, which is the northeastern region of Honshu, killing over 19,000 people.

Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings’ (TEPCO’s) Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station, which straddles the towns of Okuma and Futaba in Fukushima prefecture, was devastated by the tsunami. Seawater reaching up to 15 metres (49 feet) high surged over the facility’s seawall – which was less than half that height – and disabled its power supply and cooling systems, causing meltdowns in three reactors. More than 160,000 people living in the surrounding area were forced to be urgently evacuated, some due to homes destroyed by the earthquake and tsunami, others to escape the leaking radiation.

“At 3.36pm on March 12, images of the hydrogen explosion of Unit 1 of TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station were broadcast on TV, and for the first time, I realised: ‘We are now in serious trouble’,” says Yasuharu Hashimoto, a resident of Futaba Town.

Watching the footage from the evacuation centre, he felt as if all hope of returning home was lost.

The four reactors at the nuclear power station had to shut down due to damage from the accident, forcing authorities to take quick action to prevent the situation from getting worse. Two weeks after the earthquake, the three most affected reactors had been stabilised by pumping in water, and by July 2011, a new treatment plan was put into operation that cooled the reactors using recycled water. In mid-December of that year, it was announced that the power station had officially entered the status of “cold shutdown”.

Today, the decommissioning work at the power station continues to go full steam ahead. However, it is expected to take 30 to 40 years in total to complete the mission.

Meanwhile, the reconstruction in the Tohoku region, which includes Fukushima, has shown notable progress, after the Japanese government allocated US$209 billion to support such efforts.

“We appreciate the support after the Great East Japan Earthquake from Hong Kong citizens. For the areas affected by the tsunami, we believe that the reconstruction of infrastructure and hardware aspects is mostly complete,” says Taishi Nakami, counsellor of the government’s Reconstruction Agency, which was established after the Great East Japan Earthquake.

“The reconstruction of the areas affected by the nuclear power station accident is still only halfway complete, and mid- to long-term measures are needed,” he adds.

Although the evacuation orders have been lifted in most of the affected areas due to intensive decontamination work, there still is more work needed to bring communities back to life. “With no population growth due to the evacuation, a lack of industrial players, and unused land remaining, the challenge is how to innovate and provide a new growth model for Japan,” Nakami says.

An even bigger challenge is to dispel ongoing misconceptions that Fukushima is an unsafe place to visit and live. Here are five things you may not know about the prefecture, 12 years after the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear meltdowns.

1. Decommissioning and reconstruction in Fukushima inspire next-generation industries

In the years following the triple disasters of 2011 (earthquake, tsunami and nuclear accident), the Fukushima Innovation Coast Framework was founded to build a new industrial infrastructure in the prefecture’s coastal region. The aim of this national project is to reconstruct the industries lost due to the disasters.

Under this framework, the Fukushima Robot Test Field was developed as one of the world’s largest research and development bases. There, verification tests, performance evaluations and operational training are carried out in simulated operating conditions, mainly for ground, maritime, underwater and aerial robots that are expected to be utilised for logistics, infrastructure inspection and large-scale disasters.

In January 2021, an agreement was reached between British and Japanese companies on collaboration in research and technology deployment worth £12 million (US$13.6 million), which involved robotics and automation research to make the decommissioning work faster and safer. The joint research project, named LongOps (Long-term Operations), is funded by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), the British Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA) and Japan’s TEPCO, the operator of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station.

“The decommissioning of the power station is making steady progress, with the development of a robotic arm for removing fuel debris and various types of survey robots to assess the situation within the power station,” says Yuki Tanabe, director for International Issues, Nuclear Accident Response Office, Agency for Natural Resources and Energy.

Meanwhile, Fukushima prefecture has announced its goal of meeting all of the prefecture's energy needs – electricity, gas, oil and thermal energy – through renewables by around 2040. That includes replacing the use of oil and gas. According to the government, more than 80 per cent of the prefecture’s electricity is generated from renewable sources.

“There are various types of renewable energies, such as solar, wind and geothermal, and we believe it is important to have an appropriate energy mix,” says Kiyotaka Yamada, deputy director of Fukushima’s Revitalization and Comprehensive Planning Division.

2. Water discharge from the nuclear power station has been treatedand deemed to pose no health risk

According to the government’s plan, the water stored at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station will be treated through the Advanced Liquid Processing System (ALPS), which removes radioactive materials other than tritium. The ALPS process reduces the amount of non-tritium radioactive substances to a level that is below the regulatory standards set by the Nuclear Regulation Authority (NRA), in compliance with the recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP).

In addition, the treated water is then diluted with seawater to make the tritium concentration less than one-fortieth of Japan’s regulatory standards and less than one-seventh of the World Health Organization’s limits for drinking water. The water will be released after the concentrations of both non-tritium radioactive substances and tritium have been reduced to levels well below regulatory limits.

Tanabe points out that the offshore water discharge is necessary to make room for other decommissioning requirements that would lower the overall risk at the site. “Currently, TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station has more than 1,000 tanks for treated water, and these tanks are overwhelming the site,” she says. “As we make progress in decommissioning, we have to consider how we install temporary storage for fuel debris and other facilities at the limited site in order to move forward.”

To ensure that international safety standards are met, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has been tasked with reviewing the plans and actions related to the water discharge operation. The IAEA has also started independent source and environmental monitoring to corroborate the data on the operation.

In September 2022, an experiment began to observe marine organisms, such as olive flounders, raised in ALPS-treated water, comparing them with a control group living in seawater collected from the shore near the nuclear power station. The purpose of the exercise is to demonstrate scientifically that tritium is not concentrated in living organisms any more than the level of concentration in the rearing environment.

3. Radiation around the nuclear power station has dropped to levels safe enough for workers and visitors in the area to wear normal clothing

Most parts of Fukushima prefecture have already permitted displaced residents to return to their homes. In March 2020, East Japan Railway Company (JR East) resumed all railroad lines in the Tohoku region devastated by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami.

At TEPCO’s former Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station, radiation levels have declined significantly. In fact, workers are now allowed to wear regular work clothes and disposable face masks in 96 per cent of the facility’s designated site, as opposed to the special protective gear that they were required to wear immediately following the accident.

But Naoto Iizuka, chief technology officer for Fukushima Daiichi Decontamination and Decommissioning Engineering Company – which was established by TEPCO in 2014 – points out that it has been a long road to get to where things are today.

“The explosion of Units 1 and 3 and the tsunami scattered a large amount of debris over the power station premises, and at the time of the accident, protective clothing and full-face masks were required in areas throughout the site,” he explains.

“The workers were constantly nervous, because they had never done this work before and were unfamiliar with it.”

Iizuka admits that there has been a learning curve with the decommissioning process, as “more than a few new issues” came up, but progress continues to be made.

To prevent groundwater from seeping into the stricken power station and becoming contaminated, an investment of US$324 million was put towards building a wall of frozen soil around four of the station’s reactors. This involved inserting 1,500 tubes filled with brine 30 metres (98 feet) underground and cooling them to minus 30 degrees Celsius (minus 22 degrees Fahrenheit).

The effort has reduced the volume of contaminated water generated per day, from 540 cubic metres (142,650 gallons) to 130 cubic metres by 2021. “We will continue our efforts to reduce the volume of contaminated water to 100 cubic metres per day by the end of 2025,” Iizuka says.

Another decommissioning task calls for removing spent nuclear fuel from the affected reactor units, and work on two of those four units was completed in 2014 and 2021, respectively. Efforts are continuing to remove the fuel from the remaining two affected units, and also to retrieve fuel debris.

“Twelve years have passed since the accident, and there is a certain sense of traction now. We feel that we can look ahead, settle in our task and systematically proceed with decommissioning work,” Iizuka says.

4. Fukushima residents living near the power station were found to have suffered no health problems nor deaths from radiation

While the 2011 tsunami flooded approximately 560 sq km (216 square miles) of land and claimed more than 19,000 lives, there have been no recorded deaths from acute radiation injury resulting from the affected nuclear power station.

Screening was conducted on 195,345 Fukushima residents living in the power station’s vicinity in the weeks following the accident until May 2011, and no adverse health effects were found among them.

“In the aftermath of the earthquake, in order to reduce the health concerns of the prefecture’s residents, we have conducted a number of health surveys, developed advanced research and treatment centres, and invested in training of healthcare professionals,” Yamada says.

“We have also made efforts to strengthen measures to address the increasing number of people with metabolic syndrome, child obesity and tooth decay, as well as to promote healthy life expectancy by fostering health awareness and improve the rate of cancer screening.”

5. Evacuation-designated zones now cover less than 3 per cent of the entire Fukushima prefecture

Evacuation-designated zones were established following TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station accident, covering multiple towns and villages.

There are three categories for these zones, reflecting different levels of radiation measured in a designated area. “Difficult to return” means lodging is fully prohibited in that zone, with entry only allowed under exceptional circumstances. The “restricted residence” and “evacuation order cancellation preparation” categories largely prohibit lodging with only some exceptions allowed, but generally permit people to enter and operate businesses.

But now, restrictions in most of those areas have been lifted, either fully or partially. As of May 2021, evacuation-designated zones covered 337 sq km (130 square miles) of Fukushima prefecture – just 2.4 per cent of the region.

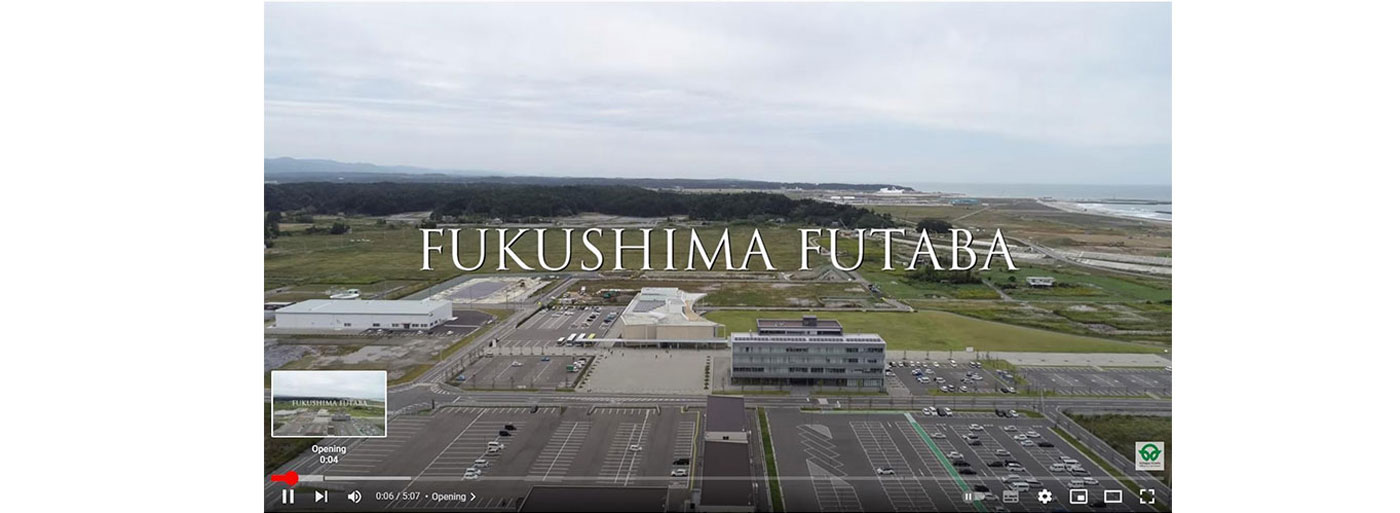

Earlier in 2022, people returned to Futaba Town, one of the towns located in the shadow of the disabled nuclear power station. This is the last of the evacuated towns in Fukushima to reopen.

“The town office of Futaba reopened on September 5, and the day before that, I returned there by myself. That filled me with tremendous joy,” says Hashimoto, who returned and works as the manager of Futaba’s Secretary and Public Relations Department. “For about six months to a year immediately after the earthquake, I lived in an evacuation centre, and there were times when I thought we might never be able to come back.”

At this point, there are only about 30 former residents in Futaba Town. According to a survey conducted in 2021 by the Reconstruction Agency and others, only a small number of those who said they would not return cited concerns about radiation as the reason for not returning. Many of them had already moved to and settled in their new communities, or their children had started school in their new neighbourhoods, Hashimoto notes.

“Some former residents say they cannot return because they will have no place to work. Other reasons include having already purchased homes in the evacuation area to which they have relocated, and their children having started school in the municipal system,” he notes.

More than a decade after having to leave their homes, some of Futaba Town’s former residents may find it a daunting task to move again.

“To help those former residents who want to return, we have been building up the town centre, restoring infrastructure and creating a safe environment for them to return, including public housing, hospitals and other facilities.”

Incentives are being offered to draw businesses back to Futaba Town – including subsidies from the Japanese government to cover two-thirds of the construction costs for buildings – and 24 companies have so far decided to set up in the reopened town. Hashimoto adds that Futaba Town is also working to attract new residents.

with the Commercial Department of the South China Morning Post.